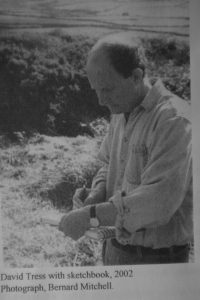

By Bernard Mitchell

Brecknock Museum and Art Gallery

September 19th 2003

David Tress 2020

Messum’s Fine Art, St Jame’s, London.

November 7th – November 27th

David Tress, ‘Land and Sea (Winter Spring)’, mixed media on paper, 52x64cm, 2018

David Tress, ‘Land and Sea (Winter Spring)’, mixed media on paper, 52x64cm, 2018

It may seem strange that a small town museum should host an exhibition of drawings by one of Wales’s great landscape artists, but there is more to the Brecknock Museum and Art Gallery than first meets the eye. Inside, your first impression is of an unchanging collection of Victorian artefacts, farm implements, and stuffed birds. The success of these monthly exhibitions is due to the dedicated enthusiasm of the Museum’s curator David Moore, who has been quietly building a national reputation for Brecon. His idea for an exhibition of the drawings of David Tress was put to Myles Pepper, owner of the West Wales Arts Centre in Fishguard, Pembrokeshire.

An expression of interest by David Moore, curator at Brecknock Museum and Art Gallery, in arranging an exhibition of David Tress’s work was the starting point of this project. Tress has been making drawings for many years, and when he suggested a show of these, David Moore responded enthusiastically. Once begun the idea of touring the show soon followed and I am delighted that, now, many more people in Wales and England will have the opportunity of seeing David Tress’s powerful and arresting drawings.

(Myles Pepper, Foreword, Lambirth 2003:7)

In a recent email David Moore said, “ I was very pleased to show an exhibition of drawings by David Tress. His paintings are well known but his drawings, an important part of his output are not. Confined to black marks of graphite and charcoal on paper, often heavily scored, these drawings have a different character to his paintings. It is challenging work in which strong lines, deep blacks and sharply contrasting white light evoke dark, disturbing landscapes. They deserve to be much more widely experienced ”.

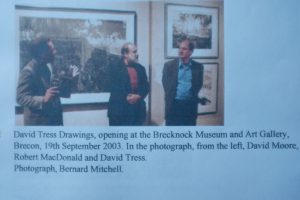

The exhibition, the first time that the drawings of David Tress have been shown to a wider audience, was opened by the artist Robert MacDonald, whose work is more reminiscent of David Jones than David Tress, to a lively audience on the 19th of September 2003. It travels over the next two years to Newport Museum and Art Gallery, The Midlands Arts Centre, Birmingham, The National Library of Wales, Aberystwyth, The Guildhall Gallery, London and ends back at the West Wales Arts Centre, Fishguard in May to June 2005. In Brecon the exhibition contained thirty one works ranging in size from 50 x 70cm. (approx) to the largest, St.Davids 1 and 11 1999, 112 x 152cm. However, in some of the larger venues, in the future, extra works will be added. Except for three early works using pencil and Indian ink on paper, in most of the works he uses graphite and charcoal on paper. The exhibition was well hung in both of Brecknock Museum’s two excellently lit rooms.

In 1983 Myles Pepper opened the West Wales Arts Centre Gallery in Fishguard with an ambitious plan to develop a national market for the best of Welsh modern art. David Tress, whose first one-man show was held at the Gallery in 1991, became a fundamental member of Pepper’s talented stable of artists. Later he began to exhibit in Cardiff and from 1995, at the Boundary Gallery in London.

Pepper did not want to be speaking just to locals, but to provide a national display case for local art, exposing it to a larger and more varied public, as well as bringing in art from further afield to fertilize and enliven the local scene. In all this the presence of Tress was a key factor.

(John Russell Taylor’s Introduction, Rendell 2002:12)

Since 1990, I had been travelling Wales, taking documentary portraits of artists and writers, and it was at the West Wales Arts Centre, Fishguard in 1994 that I first met Myles Pepper and discovered the paintings and drawings of David Tress. It was a rare and seminal experience, taking me back to childhood memories of time spent on holiday in the mystic landscape of Pembrokeshire. What Tress had achieved for me, was not only the recording of the wildness of the scenery, but the unique inner emotion of the event.

The development of Tress’s gestural style can be seen in its purest state in his black and white drawings. They are equal to his paintings in scale and ambition. The extreme tonal contrasts give them an icy sharpness, and the staccato lines move in endless counterpoint against the fatter strokes of charcoal, graphite and chalk.

( Rendell, 2002:45)

From the beginning of the nineteenth century the Welsh landscape has provided inspirational material for some of the greatest Romantic artists such as J.M. Turner. In 1792 he visited Wales for the first time. Before the turn of the century he made five tours, painting the landscape. Later artists like John Piper, Graham Sutherland and Josef Herman became immigrant workers in the Valleys and Mountains of Wales, while Stanley Spencer and even L.S. Lowry continued in the tradition of Thomas Rowlandson’s travels in Wales. Like his predecessors John Piper and Graham Sutherland, David Tress came to Pembrokeshire, arriving in 1976.

David Tress had family links to Wales. His forefathers had left South Wales to join the Welsh community in Patagonia, where his grandmother was born. After she married she returned to live at her husband’s home on Anglesey, where his mother was born in 1921. David’s parents moved to London, where, at 132 Harrow Road, Wembley, he was born in 1955. In the 1950’s Harrow was a leafy suburb, where he developed a love of nature, living the life of his favourite author Gerald Durrell, in his book, My Family and other animals.

Only later did Tress realize that his early experiences of life had been immortalised by John Betjeman, chief poet of the humble suburban landscape. The sound of the wind in the poplars by Wembley Stadium and the panorama of twinkling lights were symbols of a time when a distant sunset could still shed its rays on suburbia. Poems like ‘Harrow-on-the-Hill’ were vantage points where Betjeman contemplated the action of the weather and the bustle of suburban activity, effortlessly transmuting them into the stirring breezes and harbour lights of his beloved Cornwall.

(Rendell, 2002:16)

From an early age he had an interest in art, studying it alongside the sciences at Latymer Upper School near Hammersmith. His concern for nature and the environment motivated his interest in landscape, both urban and rural. One school trip he particularly remembers was to an exhibition in Colnaghi’s of watercolours by John Sell Cotman, whose spare style and sense of organisation gave his paintings a tension between representation and abstraction. It began for Tress a life-long interest in the effects of weather and light, as used by early nineteenth century artists. While still at school he attended a pre-foundation course at Harrow College of Art on Saturday mornings, studying painting and drawing.

As a teenager in London he had fallen in love with art, the idea and the actuality, and haunted public and West End galleries. What then particularly excited him was the work of the Abstract Expressionists, just at that time being seriously exhibited in London public galleries, and he took to painting his own abstracts: turbulent, expressionist landscapes rather than the poised, geometrical kind favoured by such British artists as Ben Nicholson and Victor Pasmore.

(Taylor, 2001:2)

On leaving school he was accepted on the foundation course at the college. In the first term it was run by Ken Howard RA. Here he developed artistic skills through the study of life drawing, perspective, colour and tone. Howard, a dedicated teacher, was a master in the use and control of light, a landscape painter following on from where Turner left off, pushing it forward into the twentieth century, a discipline that Tress would use in his later drawings and paintings in Pembrokeshire.

Any painter who admires Turner and Monet as Howard does is likely to place great emphasis on the naturalistic and pictorial revelation of light in the world. But the manner in which he seeks to grasp the essential character not only of the reflected light on objects in the world, but also the very light source itself, is perhaps peculiar to this artist among his contemporaries.

(Spender, 1997:9)

After the first term Tress began to broaden his interests, visiting the London galleries, and looking at the work of contemporary artists. Two who particularly interested him were the American Abstract Expressionists, Robert Motherwell and Willem de Kooning. In his book The Triumph of American Painting, A History of Abstract Expressionism, Irving Sandler describes the work of de Kooning and his contemporaries.

The New York artists striving in this direction – it may be called gesture painting to differentiate it from other tendencies in Abstract Expressionism – believed that their painting had contemporary significance beyond its physical attributes. Their discussions about art centered on what was expressed – on connections with their experience – rather than on formal matters. de Kooning declared:

“ Painting isn’t just the visual thing that reaches your retina – it’s what is behind it and in it. I’m not interested in “abstracting” or taking things out or reducing painting to design, form, line and colour. I paint this way because I can keep putting more and more things in it. – drama, anger, pain, love, a figure, a horse, my ideas about space. Through your eyes it again becomes an emotion or an idea. It doesn’t matter if it’s different from mine as long as it comes from the painting which has its own integrity and intensity”.

(Sandler, 1970:92)

Tress studied the Modernist theories of Greenberg, and the work of conceptual artists such as Larry Bell, David Medalla, John Baldessari and Keith Arnatt. At this time he was producing paintings by joining large sheets of paper, and spattering them with paint, stencilling and cutting into the surface geometric shapes. After finishing at Harrow, Tress was accepted on a three-year fine art course at Trent Polytechnic, Nottingham. Here the artist and writer on the theories of conceptual art, Victor Burgin, who had recently returned from the United States, was teaching. Trent Polytechnic was a hotbed of Post-Modernism, and during his time there David Tress’s work took a strange turn. It might seem even bizarre, knowing his paintings and drawings today, to imagine, that for his degree show, he made a film based on the annual Nottingham Goose Fair, with a soundtrack of noises from the fairground and a live performance of music which he had composed, based on the work of the American musician Charles Ives.

In July 1976, David Tress with his partner Patricia Luker, some watercolour paint and a tent, left Nottingham for Pembrokeshire. They travelled around the county, camping and eventually settled in a caravan behind the Boar’s Head Pub in Templeton, where Tress had begun work as a barman. They progressed to a rented holiday flat and, at last, a more permanent home at Hill Lodge Cottage near Narberth.

He spent the first ten years in Pembrokeshire developing and perfecting a style of minute, almost photographic realism. In a recent conversation he explained this sudden change in direction from conceptual art, ‘as a radical step to start from scratch again’. By 1988 he had perfected his technique to such a high standard that it was impossible for him to take it further. The last work, which he finished after three years, was the oil painting ‘The Big Rock’.

It was another change in direction, a new beginning, reflecting his early interest in Abstract Expressionism, and the use and control of light, which was to develop over coming years into the work we see today. His comment on the earlier work was that, ‘It did not allow me a way through to an emotional response to the landscape’

Again, it was discipline, as well as being about as extreme a reaction as one could imagine to his conceptual phase. But something so finicky clearly was not going to be a long term solution for one of his artistic temperament. He was by nature an independent, but a bold, rather wild independent, who could not take refuge in almost photographic realism for very long. By the time that he knew inside-out how to do it he knew more precisely what he wanted to do. Never one to pussyfoot with his materials, he began seriously to treat them rough.

(Taylor, 2001:8)

David Tress at first appears a quiet almost shy man, but underneath this calm exterior is a man who knows his own mind, has the courage of his own convictions and the strength to pursue his chosen path. The new expressive style he developed took the landscape almost to abstraction, personified in his drawings, using graphite and charcoal. Here the energy of the elements, wind, rain and sun is channelled into explosive bursts of energy, almost destroying the thick Saunders Waterford paper (300lb, 640gram) that he uses. As well as the charcoal, graphite sticks, and rubbers, a Stanley knife, screwdriver and his bare hands are all part of the arsenal of tools he uses. Often the paper is layered or torn, reflecting the physical violence of nature and depth of landscape.

In fact David Tress’s drawings, with their startling depth of image and invigorated zigzag marks, are principally about the fall of light on landscape. (He acknowledges for example a long-standing interest in low light and long cast shadows. ‘I find the landscape exciting under cloud’, he says.) There is an urgency to these images, a controlled wildness, which is utterly compelling. They are not in the least tentative, the finished drawings having a pictorial logic (a mixture of spontaneity and inevitability) which generally looks as if it is caused Tress little trouble. Yet these drawings have been endlessly worked over and revised, and more often than not suffered for.

(Lambirth, 2003:26).

I photographed David Tress for the first time in 1996, and have made several visits since to his present home, two cottages converted into one in terraced Castle Street, Haverfordwest, which he shares with his wife Marijke Tress-Braaksma. His current studio is a two-storey building, a few yards down the road from his house. The upper floor reached by a steep staircase, and lit by over head windows, is where he makes his drawings and watercolours. Downstairs, the walls are covered in paint in Jackson Pollock style.

Tress makes his drawings in the studio, working on them for several days, often putting them away and reworking them at a later date. His research is done in the field, where he spends many hours in all weathers, making quickly drawn sketches and notes in waterproof sketchbooks.

Since his move to Pembrokeshire, other artists and writers have influenced Tress. The poet R.S.Thomas wrote about the wild beauty of the country. In the poem ‘Out of the Hills’ he writes of ‘The weight of the sky, and the lash of the wind’s sharpness…’ Two painters who had earlier discovered the Pembrokeshire landscape were John Piper and Graham Sutherland. John Piper had a cottage on Strumble Head, one of Tress’s favourite places to sketch. For several years, Piper worked in the North of the County, while Sutherland visited and painted in the South.

Piper once said to me that he could not quite imagine where Sutherland had found all the twisted, tortured roots which played such a prominent role in his paintings of the period, as Piper had never seen anything similar in Pembrokeshire. Then, after a moment’s consideration, he added: ‘But of course painters find only what they are already looking for, and paint what is in their heads rather than what they see outside.’

(Rendell, 2002:12)

Tress also often visited Picton Castle, where the work of Graham Sutherland was exhibited. Sutherland, having begun as an etcher, taught himself about paint by experimenting with watercolour, as indeed Tress was to do. Oils came later. Sutherland first visited Pembrokeshire in 1934, and later claimed that it was in this West Wales landscape that he really began to learn painting. He wrote: ‘It seemed impossible here for me to sit down and make finished paintings “from nature”…The spaces and concentrations of this clearly constructed land were stuff for storing in the mind. Their essence was intellectual and emotional, if I may say so. I found that I could express what I felt only by paraphrasing what I saw…’

He continued: ‘I wish I could give you an idea of the exultant strangeness of this place – for strange it certainly is, many people whom I know hate it,

and I cannot but admit that it possesses an element of disquiet…. The whole setting is one of exuberance – of darkness and light – of decay and life.

(Lambirth 2003:27)

Tress is also aware of his contemporaries, for as in the past, there are today many landscape artists in Wales. Two of particular interest, who work in this expressive style are Peter Prendergast, who lives in Deiniolin, North Wales and the younger Daniel Backhouse, who has settled near the cliff tops of Strumble Head. Tress’s drawings echo these sentiments, in his own unique way, working on several levels, expressing both a physical and emotional vision of the landscape. To understand his work it is important to reflect on his past influences, his love of nature and landscape in his youth, the effect of early teachers such as Ken Howard and painters such as Willem de Kooning and the Abstract Expressionists. This first travelling exhibition of the drawings of David Tress, will bring his work to a wider audience.

Bernard Mitchell 2003